Perception means ‘to seize entirely’ (from Latin percipere); yet since Plato human beings have consistently doubted about the relationship between the perceived and its actual constitution. Supposedly, objects – beyond our sensory perception of them – possess an inaccessible, mysterious quality, a concealed material nature. In turn, this strangely paranoid doubt is not only a part of perception but also an essential element of being.

We all know the feeling of ‘something being wrong’. This feeling particularly arises in instances when things lose their accustomed clarity, their comforting definiteness or repetitiveness, when they appear ambiguous, unpredictable, unclear. PALOMINO is an exhibition seeking to irritate the observer’s perception and to question its intrinsic truthfulness. The works on display generate hallucinations and/or shifts of perception on a variety of levels. The exhibition also includes selected psycho-optical phenomena (geometric/optical and acoustic illusions) as well as Max Wertheimer’s „Phänomen Phi“ („Phenomenon Phi“).

The exhibition is conceived as a journey through the realm of sensory illusion. Marcel Duchamp was one of the first 20th century artists to investigate, as early as the 1920s, the scientific premises of optical illusions. The hypnotic „Rotoreliefs“ (1935) are thus prototypical for Duchamp’s examination of visual perception. The film, „Anémic Cinéma“ (1925-26), made in collaboration with Marc Allegret and Man Ray , is one of the earliest films examining visual effects whilst also being the precursor of the „Rotoreliefs“.

PALOMINO furthermore includes works by other experimental film producers. Len Lye (New Zealand) primarily became known for his films produced without a camera, but solely through direct work on the film material itself by scratching, marking, and exposing it. Anthony McCall’s „Line Describing a Cone“ is a key work of the 1970s: a projected ray of light gradually turns into an ‘immaterial’ cone in the fog-filled exhibition space. Alongside these works, paintings such as those of Bridget Riley and Victor Vasarely retrace the way in which the protagonists of Op Art have, since the 1960s, examined visual phenomena and their effect on the viewer. These are complemented by Brian Gysin’s „Dreammachine“ which literally generates visions. These works function as historical references within the context of PALOMINO.

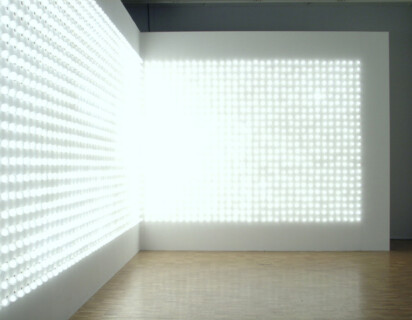

The contemporary works have also been selected on the grounds of the psychoactive effects and the influences on and modifications of the senses they produce. Carsten Höller’s „Lichtecke“ („Light Corner“), a light surface illuminated by some 2000 bulbs which, by flashing in a frequency of 7,8 Hz, create (especially with eyes closed) psychedelic colour effects. His „Umkehrbrille“ („Inversion Goggles“) enable the visitor to experience the exhibition upside down, in order to ‘view the way the world really is’, i.e. as an inverted projection on the retina. „[Oszo 3]TM“ by Ritchie Riediger thrusts the listener into a vortex of unusual acoustic sensations. In contrast, „Stilleraum“ („Room of Silence“) reverts the visitor to him/herself. A perfectly sound-insulated room seals the visitor off from all acoustic information: one hears only oneself, the rushing in one’s head, the blood flowing through one’s veins.

The hovering drops of water in Olafur Eliasson’s „Yet Untitled“ baffle the senses; his mirror, expanding from concave to convex, recalls similar drug experiences. Katarina Löfström’s film „Whiteout“ is an experiment with the spots and colours perceived by the human eye after being exposed to sunlight for too long. Henrik Plenge Jakobsen’s work enables the visitor to change his/her behaviour by inhaling laughing gas, whilst Heimo Zobernig’s broken mirror offers a myriad of fragmentary reflections of the outside world.